Solver modes

There are three solving modes in SunSolve Power:

- Single solution,

- Sweep,

- Optimisation.

In single-solution mode, the results are calculated using the input values on the many input tabs. A simulation contains a single run.

In sweep mode, the user selects certain inputs to be ‘swept’. These selected inputs are stepped from an initial value to a final value, and the results will be returned as multiple runs under the same simulation. Almost every input—even materials—can be swept.

In optimisation mode, the user selects certain inputs to be optimised and an optimisation goal, where the goal includes an ‘output metric’ and whether that metric should be maximised or minimised. SunSolve then determines the values of the selected inputs that meet the optimisation goal. This requires SunSolve to conduct multiple runs under the same simulation.

Note that SunSolve’s optimiser applies a genetic algorithm that is well suited for complicated optimisations, such as those with more than one input. A simple optimisation with a single input might be more efficiently solved with a sweep.

How to perform a sweep

Section titled “How to perform a sweep”Switch to sweep mode: Select sweep on the Solver tab.

Activate broom: Click the broom icon located on the toolbar. When the broom is highlighted, inputs can be added or removed.

Select inputs to sweep: Eligible inputs are highlighted in yellow. Click eligible inputs to add or remove them from the sweep input list.

Define sweep parameters: On the Solver tab,

- select the number of steps;

- set the initial and final values of each sweep input and whether the step intervals are linear or logarithmic, or alternatively, select the ‘fix’ checkbox and enter the values manually;

- enable two-dimensional sweeps by clicking the ↓ arrows at the start of the row (requires at least two sweep inputs).

Run sweep: Click play ▶.

Download results: Click the download icon. The results of all runs within a sweep are included in the downloaded files, unless the checkboxes labelled ‘Select run’ or ‘Download into separate files’ are checked.

How to perform an optimisation

Section titled “How to perform an optimisation”Switch to optimisation mode: Select optimisation on the Solver tab.

Activate wand: Click the wand icon located on the toolbar. When the wand is highlighted, inputs can be added or removed.

Select inputs to optimise: Eligible inputs are highlighted in yellow. Click eligible inputs to add or remove them from the optimisation input list. Up to three inputs can be selected. Unlike sweep mode, materials are not permitted as inputs.

Define optimisation input parameters: In the input section of the Solver tab, set the upper and lower bounds, the best guess, and the resolution of each optimisation input. The solver will determine the optimal values for these inputs to within the user-defined resolution.

Define optimisation goal: In the goal section of the Solver tab, select the output metric and whether the goal is to maximise or minimise that output.

The output metric can be

- the optical absorption in one or more layers (integrated over the incident spectrum),

- the cell or module electrical current, or

- the cell or module electrical power.

When the output metric is optical absorption, it is necessary to select the relevant optical layers. The output metric is the sum of the equivalent photon current absorbed in the selected layers. If a layer includes free-carrier absorption (FCA), select whether the photon current should represent the layer’s total absorption current (includes FCA) or its generation current (excludes FCA).

Set optimisation options: In the options section of the Solver tab, set limits on the optimisation routine and set inputs for the genetic algorithm. These are described below.

Run optimisation solver: Click play ▶. The solver applies a genetic algorithm to find the optimal input values that meet the optimisation goal (within the constraints of the input bounds and the optimisation options).

Download results: Click ‘Download optimisation results’ on the Solver tab to download the inputs and output metric of every run in the simulation. Click the download icon to download the various output files for the optimised run.

Optimisation routine and options

Section titled “Optimisation routine and options”We now describe the optimisation routine. The underlined words are user options.

The optimisation solver uses a genetic algorithm to find the optimal input values. This algorithm follows an evolution-based approach to find the ‘fittest’ combination of genes (optimisation inputs) over multiple generations.

The user sets the number of runs per generation . Every run is populated with all of the inputs defined on the various input tabs, except those selected as optimisation inputs (genes). The values for the optimisation inputs will be assigned by the optimisation routine.

In the first generation, the number of runs is either or , whichever is higher, where is the number of inputs being optimised. The gene values are selected so that they cover the full range between the user-defined lower and upper bounds for each input. The first generation also includes the user’s best guess.

All runs within the first generation are then solved in parallel, and the output metrics are collated. The runs with the best output metric (i.e., the fittest runs) are added to the ‘gene pool’. As the generations continue, the gene pool will always consist of the fittest runs, where the size of the gene pool cannot exceed runs in gene pool .

A second generation of runs is then created, where the gene values are selected by ‘mating’ the runs from the gene pool. This mating process involves the mix fraction and the maximum mutation Mmax. The mating process is described in more detail below.

At the completion of the second generation (and all subsequent generations), the gene pool is again modified such that it contains the fittest runs from all generations.

The generations continue until one of the following termination conditions are met:

- the user stops the simulation by clicking stop ■,

- the maximum runs is reached,

- the maximum total rays is reached

- the time limit is reached,

- the run failure threshold is surpassed, or

- the algorithm converges (defined below).

At that point, the run that gives the maximum output metric is defined as the ‘fittest’. Its gene inputs are loaded for the final run, which is solved to give the optimised results.

Termination conditions

Section titled “Termination conditions”The first four termination conditions are self-explanatory.

The fifth termination condition arises when the number of failed runs in the gene pool exceeds . A failed run occurs when there are failures within the ray tracing or electrical solving routines. If this arises, you’re welcome to send PV Lighthouse the SIM file that caused the problem and we’ll ascertain what went wrong.

The sixth termination condition, convergence, is the most desirable condition. It means that the solver found the optimal inputs (subject to the specified constraints).

The definition of convergence is complicated by the Monte Carlo approach taken by the ray tracer. Since the Monte Carlo approach is stochastic (contains randomness), we would like the uncertainty of the optimal inputs to be small relative to the uncertainty in the stochastic behaviour of a single run.

Specifically, we define convergence as

where CIGP represents the 95% confidence interval of the runs in the gene pool, CIBR represents the 95% confidence interval of the best run, and is a user-defined constant called the convergence tolerance.

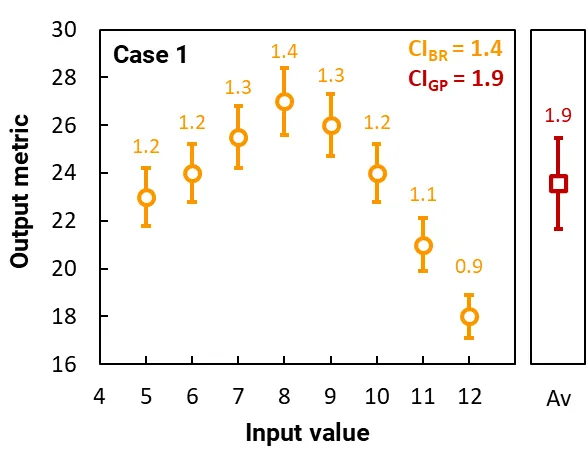

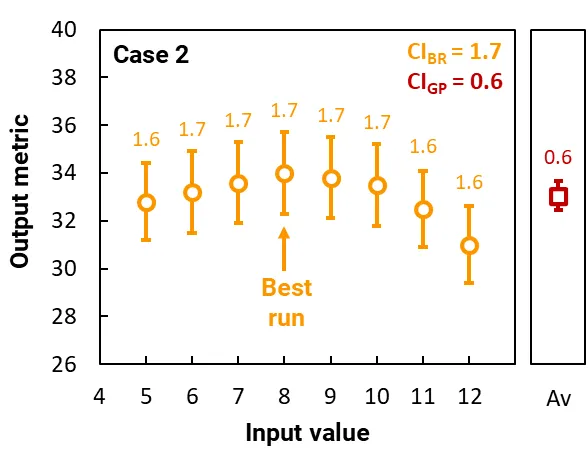

We demonstrate the meaning of this convergence condition using the graphs below.

These graphs plot the results of two separate cases. Each case constitutes a simple simulation that contains one input variable and a gene pool of just 8 runs, each with a different input value.

The orange circles plot the output metrics for each run in the gene pool, and the orange error bars (and labels) show their 95% CI. This CI arises from the stochastic nature of the ray tracing. The CI of the best run is CIBR.

The red squares plot the average of the output metrics, and the red error bars (and label) show the 95% CI of the runs in the gene pool; this CI is CIGP and it quantifies the variability in the output metric of the gene pool. (The calculation of CIGP does not depend on the 95% CI of the runs.)

In Case 1, the gene pool contains runs with highly variable output metrics, where CIGP = 1.9, which is significantly larger than the CI of the best run, CIBR = 1.4. Thus, if were set to 1, the simulation will not have converged. Another generation of runs would be populated with input values closer to 8 (the value of the best run) and the solver would continue.

In Case 2, the gene pool contains runs with a similar output metric, where CIGP = 0.6, which is significantly smaller than the CI of the best run, CIBR = 1.7. Thus, if were set to 1, the simulation will have converged. The optimal input would be 8, and the maximum output metric would be 34 ± 1.7.

Mating procedure

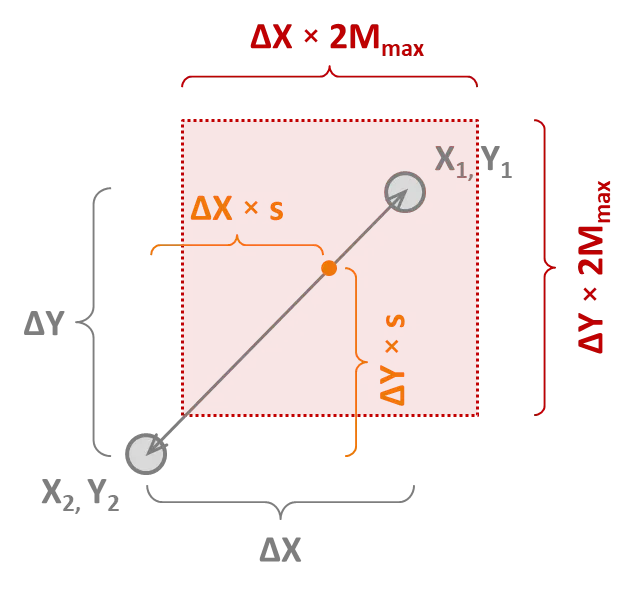

Section titled “Mating procedure”The best runs are each mated with another randomly selected member from the gene pool. This creates children whose genes are a mix of their parents’ genes. The value of those genes, i.e., their inputs, are determined by the following approach:

where R is a random number between 0 and 1, X is the input value of interest, and ΔX = X1 - X2; and where X1 and X2 are the input values of the fitter and poorer of the two parents, respectively.

The image below demonstrates this approach for a two-dimensional optimisation; i.e., when there are two input varaibles, X and Y. It depicts the two parents as grey dots within the X–Y parameter space, where X1, Y1 is the fitter and X2, Y2 is the poorer of the two parents. The new child will be randomly generated anywhere within the shaded red square of the parameter space.

Thus, a larger Mmax will lead to a greater variability in the children of the next generation. A larger Mmax will also tend towards a more robust but slower optimisation algorithm. The optimal values for s and Mmax depend very much on the problem being solved.

Finally, we mention that the algorithm clips the ‘red square’ so that it does not extend beyond the user-defined lower and upper bounds for the inputs.